Playbook

The Ground-Up CSM Playbook for Technology Startups.

Who It's For

Founders and early CSMs building customer success from the ground up.

Designed for teams before scale, not after it.

Customer success scales with systems, but it wins through human connection. Presence become the real advantage.

Purpose & Philosophy

What Customer Success Means at An Early Stage Company

I wrote this playbook because customer success is usually defined too late. Most guidance assumes a mature product, clear roles, and established systems. That is not the reality when you are early. When I was building customer success from scratch, the real challenge was not scaling. It was deciding how to show up for customers before anything was stable, and where to draw the line of overcommitment.

Early customer success is about reducing uncertainty. Customers are trying to understand whether this product is worth their time, their trust, and often their reputation internally. My job was not to make things look perfect. It was to help them reach a real outcome quickly and to be clear when the product or process was still evolving.

In practice, that meant spending time where it actually changed the result. I showed up early in onboarding, when customers were deciding if they made the right choice. I showed up when something felt off, even if there was no obvious metric to point to. I did not try to be present everywhere, and I learned quickly that constant availability is not the same as being useful.

I used systems as support, not as a substitute for judgment. Notes, reminders, and lightweight tracking helped me keep context and spot risk, but they never replaced conversations that needed to happen. If a system made it easier to avoid a hard conversation, it usually created more problems later.

This playbook reflects those lessons. It is built for founders and early CSMs who are balancing customer needs, product gaps, and limited time. It is not a fixed model. It is a set of principles I used to make consistent decisions when there was no clear playbook to follow.

Use this as a guide, not a rulebook. If customer reality contradicts what is written here, trust the customer reality. That is the point of building customer success from the ground up.

How human presence and systems work together

At my previous company, I saw what happens when customer success overcompensates for a weak product. We were extremely available. We patched issues manually, jumped on every call, and tried to smooth over rough edges with effort instead of fixing root causes. It worked in the short term. Retention stretched a bit longer. But it created the illusion that the problem was customer success execution, not the product itself.

That is a dangerous place to be. When CSMs are too present, they can mask real product issues. The company ends up investing more in coverage instead of improvement, and the feedback loop between customers and product weakens instead of strengthening.

Customer success is also one of the most tiring jobs in the modern enterprise. Customers are often frustrated. Revenue is on the line. The product team is busy or focused elsewhere. CSMs are expected to absorb pressure from all sides while staying calm, helpful, and proactive. Without support, this quickly turns into burnout.

This is where systems matter. Systems should not exist to replace judgment or reduce empathy. They should exist to reduce cognitive load. A good system helps a CSM see what needs attention, what the next step is, and what can safely be automated.

The best systems I have seen do three things well:

Make it easy to be proactive rather than reactive

Suggest or surface clear next steps

Remove repetitive grunt work that does not require human thinking

AI can and should handle much of the repetitive work, but it should operate under oversight. The goal is not to remove the CSM from the loop. It is to give them more time and energy for the parts of the job that actually change outcomes.

Human presence should be used sparingly and deliberately. It matters most when customers are evaluating trust, interpreting value, or making decisions. Systems should handle the rest quietly in the background.

If customer success is constantly filling gaps, something upstream is broken. Systems should make those gaps visible, not help hide them.

What this playbook is and is not

This is not an “exactly how to” guide. If I tried to write one, it would either be wrong for most teams or obsolete by the time it was read. Early customer success is too dependent on product maturity, customer type, and company constraints for rigid instructions to hold up.

What this playbook is instead is a record of what worked for me in practice. These are patterns I noticed, mistakes I made, and decisions that held up better than others over time. Some of them may apply directly to your situation. Others may not. That is expected.

I am intentionally not prescribing scripts, timelines, or one-size-fits-all processes. When teams follow those too closely, they often stop thinking. They optimize for compliance instead of outcomes, and customer success becomes mechanical rather than effective.

This playbook is meant to help you reason, not follow. It should give you a framework for deciding where to spend time, when to step in, and when to step back. It should help you recognize when customer success is adding real value and when it is compensating for problems that need to be solved elsewhere.

If something here does not fit your customers, your product, or your stage, change it. If your experience contradicts what is written, trust your experience. The goal is not alignment with this document. The goal is building customer success that actually works in your environment.

Who This Is For

Founder-led CS

Founder-led customer success is where most of the real learning happens. It is the period when you are closest to customer outcomes and least protected from reality. The primary responsibility at this stage is to be present at the moments that matter and to continuously collect feedback.

The critical skill is not just listening, but interpretation. Every piece of feedback needs to be evaluated and categorized. Some feedback points to a product issue. Some reveals an operational gap. Some is negligible and should not result in change. Treating all feedback the same leads to distraction. Ignoring it leads to blind spots.

Presence needs to be consistent, not reactive. It is easy to be highly engaged when a customer is new or actively happy. The harder part is maintaining regular contact once things feel stable and attention shifts elsewhere. This is often when communication drops off without anyone noticing.

A customer can be satisfied, then go quiet, and months can pass with very little interaction. That silence is often mistaken for success. In reality, confidence may be eroding slowly. When churn happens in these cases, it feels sudden, but it rarely is. It is the result of lost context and missed signals over time.

Founder-led CS works best when it creates a tight feedback loop. Customers share signals. Those signals are assessed deliberately. Changes are made when they matter, and ignored when they do not. The goal is not constant involvement, but intentional presence that keeps reality visible as the company grows.

First CSM hires

If you are the first CSM hire, you are not just inheriting a role. You are shaping a function. The systems, habits, and expectations you put in place early will be hard to undo later. Retroactive changes are almost always more expensive than doing things intentionally the first time.

The first priority is alignment. You need to understand how the founders think about customer success. What outcomes do they actually care about? Retention, expansion, product feedback, revenue protection, or something else? More importantly, what is their philosophy on what customer success should strive for? Without this clarity, it is easy to build systems that look right but optimize for the wrong thing.

Working backwards from a north star helps. Decide what success should look like for customers and for the business, then design your motions, metrics, and tooling to support that outcome. Avoid copying frameworks from other companies without understanding why they worked in that context.

As the first CSM, you will benefit from taking charge where it makes sense. Customer success has a lot of gray area, especially early on. Many scenarios will not have clear answers, and often you will not even know what you are missing yet. Waiting for perfect direction usually leads to stagnation.

Taking initiative on building systems or proposing solutions accelerates learning and builds trust. That does not mean acting unilaterally, but it does mean being willing to define a starting point and iterate. This is one of the fastest ways to grow in the role and to make customer success more durable as the company grows.

Documentation matters earlier than most teams expect. Any system you implement should be written down, even if it feels premature. Document how onboarding works, how risk is assessed, how follow-ups are handled, and how decisions are made. Update that documentation as you operate.

As product-market fit improves and the customer base grows, scaling a CS team becomes difficult very quickly without clear, process-oriented documentation. What feels like overhead early becomes leverage later. The first CSM plays a disproportionate role in deciding whether scaling feels chaotic or intentional.

Teams pre-scale or just past first traction

At this stage, customer success is starting to feel the pressure of volume. There are enough customers that intuition alone no longer works, but not enough that heavy process makes sense. The risk here is swinging too far in either direction.

Consistency becomes more important than coverage. Teams need shared definitions for onboarding, risk, and success, even if those definitions are still rough. Without them, customers receive uneven experiences and internal decision-making becomes reactive.

This is also the point where signals need to be captured systematically. Not to over-measure, but to avoid relying on memory. Quiet customers, delayed outcomes, and repeated requests should stand out early, before they turn into surprises.

Teams that navigate this stage well standardize just enough to stay aligned, while keeping room for judgment. The goal is not efficiency yet. It is maintaining clarity as traction turns into responsibility.

Defining Success Early

Customer outcomes vs feature usage

A useful outcome definition starts with what the customer is trying to change, not what they are clicking.

For example, if you sell a B2B workflow tool, success is not “the customer uses automations.” A more meaningful outcome might be “the customer reduced manual processing time for X workflow by Y percent.” Automations are a means to that end, not the end itself. A customer who sets up one automation that sticks is often healthier than one who experiments with ten and abandons them.

In a data or analytics product, feature usage might show frequent dashboard views. A real outcome would be “the customer uses data from the product to make or support decisions in a recurring meeting.” If the data is not showing up in decisions, usage alone is misleading.

For a developer platform, success is rarely “API calls per day.” A stronger outcome definition is “the API is embedded in a production system that the customer relies on.” Early usage spikes during testing do not matter if nothing ships.

In a customer support or CRM tool, logging in daily is not the outcome. Closing tickets faster, reducing backlog, or improving response quality is. If the product is not changing how work gets done, feature adoption is superficial.

Early on, I found it helpful to define success as a sentence, not a metric. Something like:

“This customer is successful if X happens consistently without us pushing.”

Feature usage then becomes diagnostic. If outcomes are not being reached, usage data helps explain why. If outcomes are being reached, lower usage is not a problem.

When teams reverse this, they end up optimizing behavior instead of results. Defining outcomes clearly early keeps customer success aligned with real value, even when the data is incomplete.

What “value realized” looks like before metrics are perfect

Early on, value realized rarely shows up cleanly in dashboards. Metrics lag reality, and in some cases they never fully capture it. Waiting for perfect measurement before deciding whether customers are getting value is a mistake.

Before metrics are solid, value realized shows up in behavior and language. Customers reference the product without being prompted. They change how they work because of it. They defend the product internally or bring it up in planning conversations. These signals are qualitative, but they are not vague.

Another sign is reduced friction. Customers ask fewer “how do I” questions and more “can we” questions. The conversation shifts from basic usage to application. When customers start thinking about what else the product can enable, they have already crossed an important threshold.

Value realized also shows up in dependency, not excitement. Early enthusiasm can be misleading. A stronger signal is when a customer would have to actively undo something to stop using the product. If removing the product creates work or risk, value is being realized, even if usage is modest.

In the absence of clean metrics, consistency matters more than intensity. A customer who quietly gets value every week is healthier than one with sporadic spikes of activity. Early CS work should pay attention to patterns, not peaks.

The role of customer success at this stage is to recognize these signals and name them. When you can clearly articulate how a customer is better off, even without perfect numbers, you are closer to the truth than any dashboard alone.

Aligning CS goals with company stage

Customer success goals should change as the company changes. Problems arise when CS goals stay static while the business moves on. What mattered at ten customers is not what matters at one hundred.

Early on, CS goals should be tightly tied to learning. The priority is understanding why customers buy, what gets them to value, and where they get stuck. Retention matters, but it is often a lagging indicator. Optimizing too early for renewals can hide product gaps and slow real progress.

As the company gains traction, the focus shifts toward consistency. CS goals should reinforce repeatable outcomes. Onboarding should reliably lead to value, and risk should be visible before it turns into churn. This is when clearer definitions of success start to matter more than raw insight.

Once revenue becomes predictable, CS goals can expand to efficiency and growth. At that point, retention, expansion, and coverage models make sense. But introducing these goals too early pulls CS into operational optimization before the foundation is stable.

What CS Engagement Should Actually Look Like

Great, now that you have an idea of what success should look or feel like, now I can provide a general heuristic for what CS engagements look like.

Onboarding:

Onboarding is about getting to a first meaningful outcome, not completing setup. The goal is to help the customer understand how the product fits into their workflow and to remove early uncertainty. Presence matters most here because assumptions form quickly and are hard to reverse later.

Early Adoption:

After onboarding, engagement should taper but not disappear. This phase is about confirming that value is actually being realized, not just that features were used. Check-ins should focus on outcomes, blockers, and confidence, not status updates.

Ongoing Use:

Once the product is part of the customer’s routine, engagement should be lighter and more intentional. Systems should handle most monitoring. Human involvement should be triggered by changes in behavior, risk signals, or upcoming decisions, not by a fixed cadence.

Moments of Risk or Change:

This is where CS should lean in. Declining engagement, shifting goals, internal changes, or product limitations all warrant direct involvement. These moments benefit from context and judgment, not automation.

Renewal and Expansion:

Renewals should not be the first time value is discussed. By the time a renewal comes up, the outcome should already be clear. Expansion, when it makes sense, should follow demonstrated value, not be forced as a sales motion.

The throughline is intentional presence. CS should show up where engagement changes outcomes and stay out of the way where it does not.

Customer Segmentation and Coverage

Who gets high-touch, low-touch, or founder involvement

Segmentation is not about fairness. It is about leverage. Not every customer should receive the same level of attention, and pretending otherwise usually leads to burnout and diluted impact.

High-touch engagement should be reserved for customers where outcomes are complex, stakes are high, or learning value is significant. These are often customers with larger contracts, strategic use cases, or unclear paths to value. High-touch does not mean constant contact. It means deliberate involvement at moments that influence success.

Low-touch engagement works when the path to value is clear and repeatable. These customers benefit more from good onboarding, clear documentation, and system-driven follow-ups than from frequent calls. Forcing high-touch engagement here often creates unnecessary dependency.

Founder involvement should be intentional and time-bound. It makes the most sense early on, with customers that are shaping the product, pushing edge cases, or representing the future ICP. Founder presence is valuable for signal, not support. If founders are repeatedly stepping in to solve routine issues, it usually points to a product or process gap.

Coverage models should evolve. A customer may start high-touch and move lower as confidence builds. Others may escalate temporarily during moments of change. Segmentation should be revisited regularly, not set once.

The goal is not to maximize coverage. It is to allocate attention where it changes outcomes and produces learning that compounds.

How to segment without over-engineering

At an early-stage B2B SaaS company, segmentation can start with three buckets that answer one question: where does attention change the outcome?

High-touch

A customer with a new or non-obvious use case, where success depends on adapting the product to their workflow. The path to value is unclear, and failure would likely lead to churn or strong negative feedback. This customer benefits from intentional check-ins and direct problem-solving.

Low-touch

A customer using a well-understood use case with a clear onboarding path. They know what they want, move quickly, and reach value without much intervention. Forcing frequent calls here adds little value and often slows them down.

Founder-involved (temporary)

A customer pushing the edges of the product or representing a future ideal customer profile. Founder involvement here is about learning and direction-setting, not support. Once the learning stabilizes, involvement should taper.

What makes this work is not the labels, but the flexibility. A customer may start high-touch during onboarding, drop to low-touch once stable, and briefly escalate again during a renewal, internal change, or product shift.

The example holds as long as it stays lightweight. The moment it requires rules to defend it, it has gone too far.

The Customer Journey

Pre-sale context and handoff

Most customer success problems start before CS formally begins. Early on, especially in founder-led setups, pre-sale and post-sale are often handled by the same person. That can hide the need for a handoff, but the risk still exists.

Even when it is the same person, context needs to be made explicit. Why the customer bought, what problem they expect to solve, and what success looks like in their words should be written down. Relying on memory does not scale, and details fade faster than expected.

As soon as another person becomes involved, any gaps show up immediately. Assumptions made during the sale turn into misaligned expectations during onboarding.

The goal is continuity. Whether the handoff is to yourself or to a CS team, the customer should feel like the company remembers the full context. When that happens, onboarding can focus on outcomes instead of re-discovery.

Onboarding motions that drive early wins

Onboarding should be designed to create confidence, not to complete a checklist. The goal is to get the customer to a real win as quickly as possible, even if that win is narrow in scope. Showing everything early usually slows progress and creates confusion.

Effective onboarding starts by anchoring on why the customer bought and mapping that to one clear use case. Structure matters, but flexibility matters more. A defined path to value helps maintain momentum, while conversations should adapt to what the customer actually needs, not what the script says.

Early wins do not need to be impressive, but they must be real. A workflow that saves time, a report that gets used in a meeting, or a task that no longer requires manual effort. If the customer’s behavior does not change, the win does not count.

Onboarding is complete when the customer can reach value without guidance. That moment, not feature coverage, is the signal to step back.

Adoption, expansion, and renewal phases

After onboarding, the focus shifts from activation to consistency. Adoption at this stage is about repeatable value, not increased usage. CS involvement should become lighter as confidence grows, with systems monitoring for changes in behavior or outcomes.

Expansion should be a consequence of value, not a goal on its own. When customers clearly rely on the product and see it as essential, expansion conversations feel natural. Pushing expansion before this point creates pressure and weakens trust.

Renewals should never be the first time value is discussed. By the time a renewal is approaching, both sides should already understand what the product enables and where it falls short. Renewals become risky only when confidence has eroded quietly over time.

CS engagement across these phases should remain intentional. The goal is to build a long-lasting relationship that compounds over time, without requiring constant manual effort from the CSM to sustain it.

Core CSM Motions

Onboarding calls

Focus on aligning on outcomes and getting to a first win. Avoid feature walkthroughs unless they directly support the customer’s primary use case. Whenever possible, define a simple, testable success statement. If we can improve X by Y percent, the impact is Z. Onboarding should be oriented around making that statement true.

Success check-ins

Use check-ins to validate that the original success statement still holds. Be explicit about whose definition of success you are measuring against, whether it is your point of contact, their manager, or another stakeholder. Misalignment here is a common source of hidden risk. These conversations should confirm impact, surface changes in priorities, and reset expectations when needed, not report status.

Risk identification and recovery

Risk should be treated as a process, not an event. Start by identifying early signals: reduced engagement, delayed responses, stalled outcomes, or changes in tone. Do not wait for usage drops alone.

Once a signal appears, make it explicit. Name the risk internally, then validate it with the customer through a direct conversation. Ask what has changed, what feels harder than expected, and whether the original success criteria still apply.

Recovery should be scoped and concrete. Re-anchor on one achievable outcome, agree on a short path to get there, and set a clear checkpoint.

Expansion conversations

It is debatable whether expansion should sit with CS at all — I personally don't think it should be. However, if it does, the role of the CSM is not to sell, but to frame opportunity based on proven value.

Expansion conversations should only happen after outcomes are clear and consistent. The CSM’s job is to connect what the customer already relies on to what additional value could exist, not to introduce net-new promises. If the customer is not confident in the core use case, expansion will feel forced and erode trust.

When handled well, expansion feels like a continuation of success, not a new pitch. When handled poorly, it turns CS into a sales proxy and distracts from the primary responsibility of ensuring value is realized.

Renewal preparation

Renewals should be a shared responsibility between CS and sales, with clear ownership. CS owns the narrative of value and risk. Sales owns the commercial process.

Preparation starts well before the renewal date. CS should document outcomes achieved, gaps that remain, and any unresolved risks. Nothing discussed at renewal should be new information.

Alignment with the salesperson matters. Both sides should agree on account health, stakeholder sentiment, and the renewal path. If CS and sales are surprised by different things, the customer already felt that disconnect earlier.

A good renewal feels like confirmation, not negotiation. When value has been consistently reinforced and expectations have been managed honestly, the renewal conversation becomes straightforward rather than defensive.

Systems That Support, Not Replace, Humans

Lightweight tooling principles

When you are a small, scrappy team, it is easy to want AI to do everything for you. Time is limited, customers are demanding, and automation feels like leverage. The mistake is using tools to replace judgment instead of reducing effort.

The goal of tooling is not to remove the human touch. It is to make it scalable. A good system should let a CSM deliver the same quality of engagement to fifteen or twenty customers that previously required five, without cutting corners or losing context.

The best analogy I have for this is driving a Tesla on full self-driving through downtown San Francisco. You are still paying attention, still responsible, but you are not burning the same mental energy on every micro-decision. You arrive less drained, even though the route was just as complex.

That is what good CS tooling should feel like. You are in the loop, aware of what is happening, and ready to intervene, but you are not expending unnecessary brain calories on reminders, note-taking, or pattern detection.

Use systems that surface what matters, suggest next steps, and handle repetitive work quietly in the background. Avoid systems that create distance from customers or give a false sense of control. The right tools make human judgment more effective, not optional.

Notes, follow-ups, and internal visibility

Notes are not busywork. They are how context survives beyond a single conversation. Early on, most CS risk comes from information living in someone’s head and disappearing when priorities shift.

Good notes capture decisions, expectations, and open questions. They should make it obvious what was agreed to, what success looks like, and what needs to happen next. If someone else cannot step into the account and understand the current state quickly, the notes are not doing their job.

Follow-ups should be explicit and owned. Systems should surface them automatically so CSMs do not rely on memory. This reduces dropped balls and frees up attention for higher-value work.

Internal visibility matters because CS does not operate in isolation. Product, sales, and leadership should be able to see patterns without sitting in every call. When notes and signals are shared clearly, CS stops being a support function and becomes an input into company direction.

Know Their Favorite Whiskey

At the end of the day, people like working with people they like. Customer success is no different. Trust is built through outcomes, but relationships are strengthened through small, human details.

When a customer shares something personal, it matters. Not in a performative way, but in a remembering way. I once had a customer mention that their dog was scheduled for TPLO surgery at the end of the month. I made a note of it. When the time came, I sent a short message wishing them well. The response was immediate and genuine. From that point on, they were noticeably more open about internal dynamics and far more transparent about what the upcoming renewal might look like.

CSMs often underestimate how much personal information comes up at the edges of calls. It shows up in casual questions like “How are you?” or “Any plans for the weekend?” These details are easy to miss and even easier to forget, but they compound trust over time.

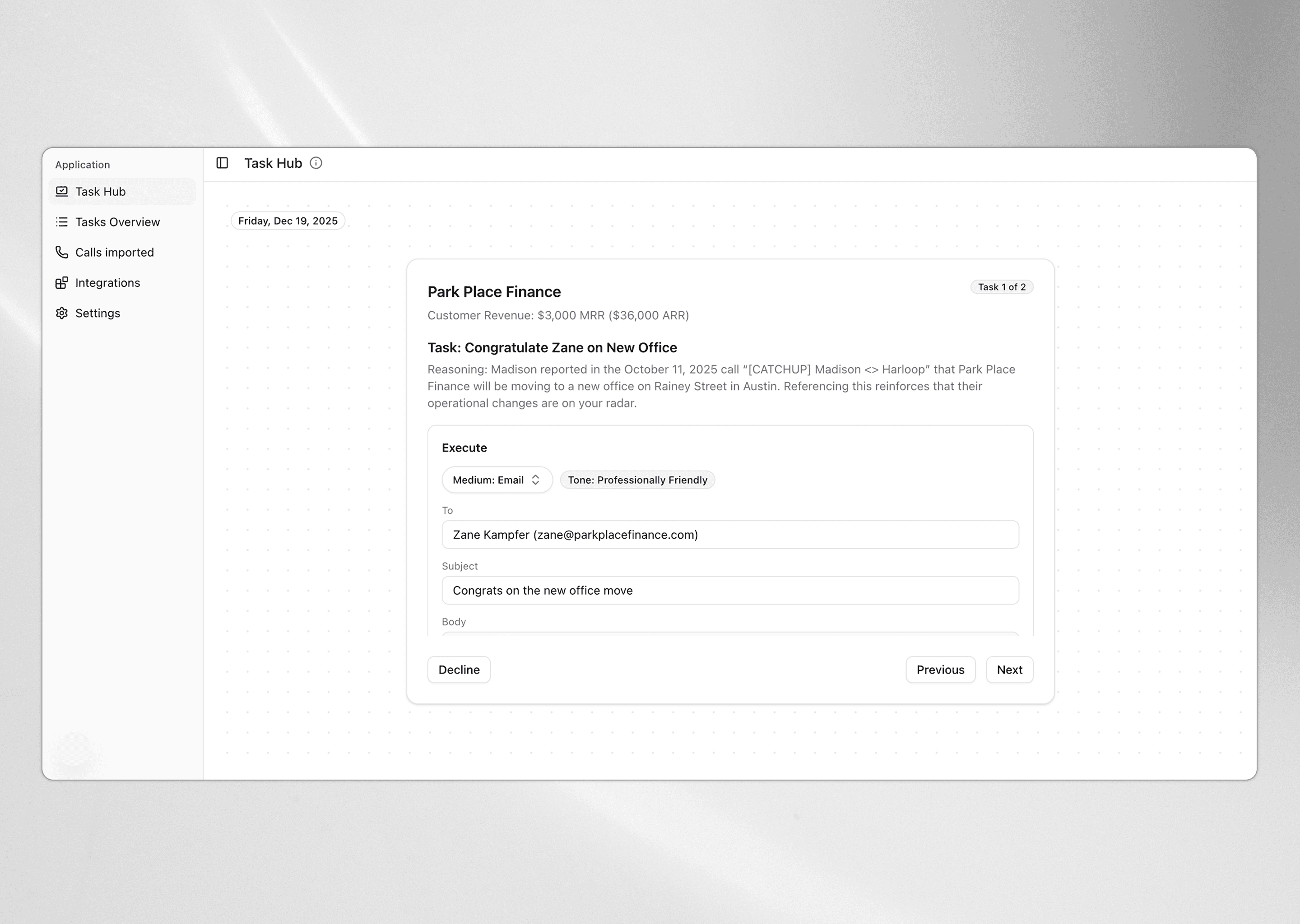

There is real enterprise value in remembering these things, especially as account load increases. That is where tools like Cuelock fit naturally. Cuelock acts as a digital brain for CSMs, capturing these cues and surfacing them at the right moment. It allows teams to maintain genuine, human relationships at scale, regardless of how large the CS organization becomes.

The goal is not to manufacture rapport. It is to respect what customers share by remembering it and showing up accordingly.

Communication Standards

How often to show up

There is no universal cadence that works for every customer. Frequency should be driven by need, risk, and stage, not by a calendar.

Early in the relationship, showing up more often is usually correct. Customers are forming opinions, learning how to use the product, and deciding how much to invest. As confidence increases, presence should become more intentional and less frequent.

Silence is not automatically a problem, but unexamined silence is. Long gaps without interaction should be a conscious choice, supported by signals that the customer is stable and getting value. When those signals are missing, reduced contact often turns into surprise churn.

Separate from cadence, context always matters. If you remember something personal, like their favorite football team winning a playoff game or a natural disaster affecting their city, say something. These moments cut through formality and reinforce that the relationship is real. A short, thoughtful note often goes further than another scheduled check-in.

The goal is to stay visible without being intrusive. Customers should feel supported and remembered, not managed.

What “good” outreach looks like

Good outreach has a reason. It is timely, relevant, and grounded in the customer’s reality. If you cannot explain why you are reaching out now, the customer will feel that immediately.

The best outreach connects to something concrete: a recent conversation, a change in behavior, an upcoming decision, or a stated goal. It should make it clear what prompted the message and what, if anything, you are asking for.

Brevity matters. Clear intent matters more. A short note that respects the customer’s time will almost always outperform a long, generic update.

Good outreach also leaves room for response. It invites confirmation, correction, or context rather than pushing information. When outreach feels helpful instead of obligatory, customers are more likely to engage honestly.

Measuring What Matters

Early indicators of retention and growth

Retention and growth rarely appear suddenly. They are preceded by signals that show up weeks or months earlier, if you are paying attention.

Early indicators often look like consistency. Customers using the product in the same way over time, referencing it in planning conversations, or building workflows around it are showing commitment. These behaviors usually matter more than short-term spikes in activity.

Another signal is initiative. Customers who proactively ask how to go further, bring new stakeholders into conversations, or suggest ways the product could expand into adjacent use cases are signaling growth potential.

Silence can be an indicator too. Not all quiet accounts are at risk, but unexplained disengagement is worth investigating. When communication drops without a clear reason, confidence is often slipping before revenue follows.

The goal is not to predict churn perfectly. It is to notice directional changes early enough to act while there is still room to influence the outcome.

Scaling Thoughtfully

What to standardize first

When scaling customer success, the instinct is often to standardize everything at once. That usually creates rigidity before clarity. The better approach is to standardize only what removes confusion and prevents avoidable mistakes.

The first things worth standardizing are definitions and handoffs. What does success mean for a customer. What qualifies as risk. What information must be captured when a customer moves between stages or owners. When these are inconsistent, scale amplifies the problems.

Next, standardize the core motions, not the conversations. Onboarding structure, follow-up expectations, and renewal preparation should be predictable, even if the execution varies. This gives new team members a clear baseline without scripting them into unnatural behavior.

Documentation should also be standardized early. Not to lock in process, but to preserve learning. What worked, what failed, and why decisions were made should be written down while context is still fresh.

Avoid standardizing judgment too early. If a process exists mainly to enforce compliance rather than improve outcomes, it is probably premature. Standardize what creates alignment and leverage. Leave room everywhere else.

What should stay human as long as possible

Conversations about value, risk, and change should remain human. Customers need to feel heard, not processed. Tools can support these moments by providing context, but they should not replace direct engagement when interpretation is required.

Expectation-setting also benefits from staying human. Early-stage products change quickly, and customers respond better to honest, contextual explanations than to templated updates.

Relationship-building should remain human as well. Details around tone, timing, and personal context are difficult to automate without losing authenticity. This is where tools like Cuelock are most effective. Cuelock does not replace the relationship. It helps preserve it by capturing cues, context, and signals so CSMs can show up thoughtfully at the right moments.

As teams scale, the goal is not to remove people from the process, but to protect where they add the most value. Automate the work that drains energy. Use systems like Cuelock to support human judgment, not bypass it.

Common scaling mistakes

The most common mistake when scaling CS is optimizing for efficiency before value is consistent. Teams add process, automation, and coverage models to solve problems that are actually rooted in unclear outcomes or weak product fit.

Another mistake is freezing systems too early. What worked at ten customers gets locked in at fifty, even though the context has changed. This makes CS brittle and resistant to learning, instead of adaptive.

Teams also tend to over-automate relationship moments. Automated check-ins, renewal reminders, or risk emails can create the illusion of coverage while trust quietly erodes. Customers feel managed instead of supported.

Operating Principles

Decision-making guidelines for CSMs

Early-stage CS requires judgment more than compliance. Most situations will not have a clear right answer, so decisions should be guided by outcomes rather than rules.

When deciding what to do, start by asking what action most directly helps the customer reach their defined success. If an action feels busy but does not move the customer closer to value, it is likely unnecessary.

Be clear about tradeoffs. Helping one customer extensively often means less attention elsewhere. That is acceptable when the learning or impact justifies it. It is a problem when effort is driven by discomfort or urgency rather than importance.

When in doubt, favor clarity over speed. It is better to pause and align on expectations than to act quickly and create confusion. Good decisions in CS are usually the ones that reduce uncertainty, even if they take longer.

These guidelines are meant to support judgment, not replace it. If a decision feels wrong despite following process, trust that instinct and reassess.

How to Prioritize When Everything Feels Urgent

Urgency in customer success is often emotional, not factual. Customers are upset, revenue is visible, and everything can feel like it needs attention immediately.

Start by grounding on impact. Ask which action, if taken today, most changes the customer’s outcome or confidence. Prioritize work that reduces risk or moves a customer closer to their defined success, not work that simply quiets noise.

Separate urgency from importance. A loud issue with low long-term impact should not displace a quiet signal that threatens retention. When in doubt, prioritize situations where uncertainty is increasing.

Use time horizons to break ties. What matters this week outweighs what matters today if the long-term risk is higher. Short-term relief that creates long-term confusion is rarely worth it.

Finally, protect focus. Doing fewer things well is better than reacting to everything. Good prioritization in CS is less about speed and more about choosing where attention actually changes the outcome.

When to break the playbook

The playbook exists to create consistency, not to override judgment. There will be moments when following it produces the wrong outcome.

Break the playbook when the customer’s reality does not fit the assumptions behind it. Unusual use cases, high-stakes situations, or important learning opportunities often justify deviation.

It is also appropriate to break the playbook when following it would delay clarity. If a direct conversation, an unscheduled call, or an unconventional approach will resolve uncertainty faster, use it.

What matters is intent. Deviations should be deliberate and understood, not reactive or habitual. When you break the playbook, document why. Those exceptions often point to where the playbook needs to evolve.

The goal is not adherence. It is effectiveness.

Appendices

Call agendas

What Customer Success Means at An Early Stage Company

Email templates

What Customer Success Means at An Early Stage Company

Health signal examples

What Customer Success Means at An Early Stage Company

Early-stage CS checklists

What Customer Success Means at An Early Stage Company